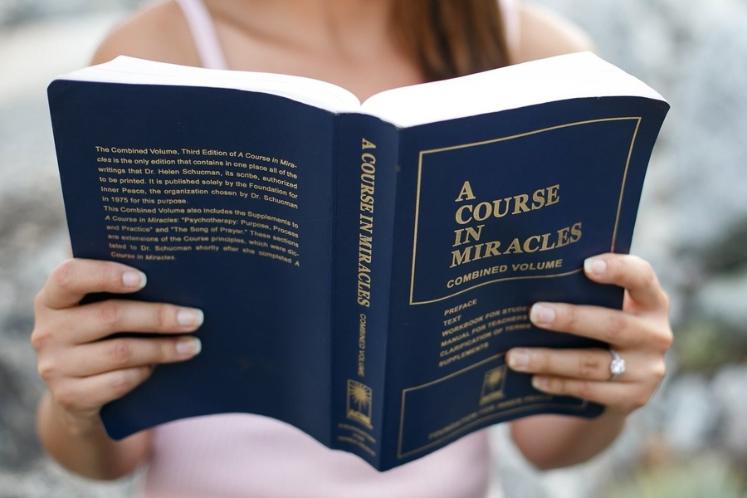

Regardless of whether you are teaching a course in a semester, a quarter, a summer session or any other a course in miracles, you need to strategically plan the various readings that you will be having the students do. Some thoughts to consider as you’re doing this planning include the following:

As you think about upcoming courses you’ll be teaching and so you are ready when you start to prepare your syllabus, dedicate a shelf, file drawer or milk crate to resources for each course. Once you have this dedicated space, you can drop in the texts you are considering adopting for the course, journals with flagged pertinent articles, a note pad with ideas to include, handbooks, software, etc. Then, as you proceed with your detailed course planning and your individual class sessions, you can use this resource to finalize your planning. Note: It also makes sense to set up a folder in your computer for pertinent materials and websites that you have identified for potential use.

Many colleges or universities expect professors to choose or “adopt” textbooks for their own particular sections of a course, while other institutions embrace a universal adoption for all sections of the same course. However, if you must make a decision about what textbook to use, then go through the process below to help you make a selection. Contact the textbook representatives to tell them the topic of the course for which you need to select a book. Request that examination copies be sent. Once the review copies have arrived, begin to compare and contrast them. In most cases, only the most current books should be considered because of the rapidly expanding knowledge base in most fields.

Determine whether the books are in their first edition, or if they are in subsequent editions. Just because a book is in its first edition does not make it less desirable than one that is in its 7th edition, but it is worth taking this into account as you make your decision. Sometimes the new book from the new author is the most fresh and appropriate for your course; other times, the tried and true book is the superior one for your purposes.

Now, begin looking at the various books’ tables of contents. How well do the topics seem to match up with what you plan to be teaching? The order doesn’t have to be the same, but there needs to be a reasonable correspondence between your topics and the topics in the book. Next, choose one or two particularly difficult concepts that you teach and find the explanations of those concepts in the textbooks you are still considering. Keep going through this process until you are satisfied that the book you are choosing does an excellent job of elucidating key concepts for your students.

Depending on your discipline, the textbook you are choosing may also have certain other features that must be evaluated. Remember that you are choosing the book for student use – so appraise all aspects of the book from a student’s point of view. Once you have reached a decision, work through the ideas below, which also apply when the book has been pre-chosen for you.

Review the textbook as thoroughly as possible. Decide which of the chapters or sections you want to use. If you ask students to purchase a particular textbook, plan to use a significant portion of it. In this day of $100+ textbooks, students expect to get their money’s worth from their purchases. If they buy a book, then find that the professor is using only a small portion of it, they feel rightfully “gypped.” Also, telling students to “just read along in the text for background,” without having any specific assignments or expectations related to that reading, is interpreted by students to mean that reading the book is not vital. Your presentation of the book and your expectations tied to it should be clarified at your first class meeting, and is more thoroughly addressed in other articles.

After determining the parts of the book that you plan to use, begin to match the reading selection with the particular week you will be addressing the content. Decide whether or not you want students to have read the material before they come to class, or whether you want them to read the material after you have introduced the material in class first. Begin adding this information to your syllabus.

At this point, formulate a strategy for how students will be held accountable for the reading. Myriad possibilities are shared in other articles, but at this juncture start to think about whether a chapter lends itself well to a quiz, to a structured discussion, to a linked activity, etc.

In recent years, many professors have created “course packs,” a collection of instructor-developed materials and/or articles from journals and other sources that are more current than the material that is included in the typical textbook. Creating course packs that use materials from a variety of sources involves making selections and securing permission to reproduce the items for students. This can be relatively time consuming, and there are a number of companies who can simplify the process. While course packs might be more expensive or limit the range of choices, they have benefits as well.

Whether you have an extensive course pack of readings and learning activities for your students or not, it is highly likely you will have some supplementary materials that you want to use. Begin developing a file of these materials. In the section of your syllabus labeled “Readings,” be sure to give all the information that students might need to locate and/or purchase the materials. If you reserve readings in the library (also known as a knowledge center on many campuses), critical information about its policies and procedures should probably be noted. When additional readings are assigned, provide students with a brief rationale, e.g. currency of information, for their inclusion.